From Avoidance to Accountability: A New Paradigm for Mineral Governance in the Great Lakes Region

Executive Summary

The prevailing international framework for managing mineral supply chains originating from conflict-affected and high-risk areas—a framework predicated on voluntary corporate due diligence and third-party auditing—is fundamentally broken. The recent legal actions initiated by the government of the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) against Apple Inc. do not represent an isolated corporate dispute; they signify a systemic breaking point. This report contends that corporate policies of disengagement or “de-risking,” such as Apple’s 2024 directive to suspend sourcing of tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold (3TG) from the DRC and Rwanda, are operationally non-credible. Such policies are rendered untenable by the geological and market realities of critical minerals and serve only to abdicate corporate responsibility, pushing the illicit trade further into opaque, ungoverned spaces. This approach fails to address the root causes of conflict and deprives local communities of legitimate economic opportunities.

The international community must therefore pivot from the demonstrably inadequate model of voluntary auditing toward a binding, state-to-state certification system. This report posits that the proven, albeit imperfect, mechanics of the Kimberley Process (KP) Certification Scheme for rough diamonds offer the most viable and effective model for this necessary transition. The KP’s record is clear: since its implementation in 2003, this binding, state-to-state certification scheme has been instrumental in reducing the share of conflict diamonds in global trade from approximately 15% in the late 1990s to less than 1% today, primarily by coupling market access to enforceable, government-issued certificates and a system of peer monitoring.

The pathway for implementing a similar system for critical minerals already exists. The institutional framework of the International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) and its Regional Certification Mechanism (RCM) provides the essential foundation. By integrating the KP’s core principles—government-validated export controls, tripartite oversight by states, industry, and civil society, and mandatory conditions for market access—the RCM can be transformed into a fit-for-purpose certification scheme for 3TG, cobalt, and other minerals vital to the global technology and energy transitions.

The ultimate objective of this proposed paradigm shift is to create a robust international regulatory architecture that makes the laundering of conflict minerals both economically and legally unviable. Such a system would finally ensure that the immense mineral wealth of Africa’s Great Lakes region can serve as a catalyst for peace, sustainable development, and shared prosperity, rather than a perpetual source of conflict and human suffering. The practical path forward is not avoidance, but verifiable, lawful engagement.

The Unraveling of Voluntary Due Diligence: A Case Study of the Apple-DRC Dispute

The current model of corporate self-regulation in mineral supply chains, championed for over a decade, is facing a crisis of legitimacy. This crisis is vividly illustrated by the escalating dispute between the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Apple Inc., a confrontation that exposes the structural flaws of a system built on voluntary audits and corporate assurances. The case serves as a critical inflection point, demonstrating that industry-led due diligence mechanisms are insufficient to sever the link between mineral extraction and conflict financing, ultimately compelling a re-evaluation of the entire global approach to mineral governance.

The Catalyst: DRC’s Legal Offensive against Apple

In late 2024, the government of the DRC initiated an unprecedented legal challenge, filing criminal complaints against Apple’s subsidiaries in France and Belgium. This move marked a significant departure from previous diplomatic and policy-based efforts, representing a direct legal assault by a sovereign state against one of the world’s most powerful corporations within foreign jurisdictions. The gravity of the allegations underscores the DRC’s profound loss of faith in the existing voluntary systems.

The complaints accuse Apple of incorporating illegally mined minerals into its supply chain, specifically alleging that these minerals are sourced from eastern DRC, smuggled through neighboring Rwanda with the assistance of the M23 rebel group, and subsequently laundered into the global market. The legal filings detail a range of serious charges, including the harboring of war criminals, money laundering, and deceptive commercial practices designed to mislead consumers into believing its supply chains are “clean” and conflict-free. By taking this action, the DRC government is not merely seeking damages; it is challenging the veracity of the entire corporate social responsibility narrative that has dominated the “conflict minerals” discourse. The lawsuit posits that despite years of corporate pledges and third-party audits, the fundamental problem of illicit mineral flows financing armed conflict persists, with devastating consequences for the Congolese people. This legal strategy signals a clear message to the international community: the era of accepting corporate assurances at face value is over, and the demand is now for legally enforceable accountability.

Apple’s Response: The “Suspension” Directive as a De-Risking Strategy

In the wake of these legal challenges, Apple publicly announced that it had instructed its suppliers to suspend the sourcing of 3TG from the DRC and Rwanda. According to the company’s 2024 Conflict Minerals Report filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), this notification was issued to suppliers in June 2024. Apple’s stated rationale for this directive was the escalating regional conflict, which, in its view, made it “no longer possible for independent auditors or industry certification” to function effectively and provide credible assurances.

However, a closer examination of the timeline reveals a more complex motivation behind the directive and its public disclosure. The internal directive was issued in June 2024, yet it was not widely publicized or reported until December 2024 and January 2025, precisely when the DRC’s criminal complaints were being filed and gaining international media attention. This sequence of events strongly suggests that the public announcement was less a proactive measure of ethical sourcing and more a reactive legal and public relations strategy. By highlighting a decision made months earlier, Apple was able to construct a defensive narrative. The company could publicly claim it was no longer sourcing the minerals in question, thereby attempting to preemptively deny the DRC’s allegations of ongoing complicity in the trade of “blood minerals”. This transforms the directive from a straightforward policy adjustment into a strategic tool in a high-stakes legal and reputational battle, illustrating how corporate “responsibility” measures can be deployed to mitigate legal risk rather than to fundamentally resolve supply chain problems.

This strategic response also exposes a deeper contradiction that strikes at the heart of the voluntary due diligence system. For a decade, Apple has consistently reported to the SEC that 100% of the identified 3TG smelters and refiners in its supply chain participated in independent third-party audits, a key metric of compliance under the U.S. Dodd-Frank Act. These reports created a public image of total oversight and control over its supply chain. Yet, the DRC’s lawsuit alleges that these very supply chains, supposedly validated by years of audits, remain deeply contaminated with conflict minerals.

Apple’s justification for the suspension—that the audits are no longer reliable due to conflict—is an implicit but powerful admission of the system’s inherent weakness. It concedes that the entire voluntary framework, which relies on audits conducted by industry-backed programs like the Responsible Minerals Initiative (RMI), is incapable of providing a genuine guarantee against the laundering of minerals from conflict zones. An audit can verify that a smelter has a due diligence policy on paper, but it cannot effectively police the fungible and often illicit flow of raw materials from thousands of artisanal mine sites through a complex network of intermediaries. The system, as it stands, is better designed to provide corporations with plausible deniability than it is to deliver foolproof accountability. Apple’s de-risking strategy, therefore, is not just a response to a specific legal threat; it is a tacit acknowledgment that the voluntary due diligence model it has long championed has failed.

The Fallacy of Disengagement: Market Realities and the DRC’s Centrality in Global Tech

The strategy of corporate disengagement, presented as a responsible “de-risking” measure, is not only a flawed ethical response but also an operationally non-credible proposition at the scale required by the global technology and energy sectors. A rigorous analysis of global mineral markets reveals that completely avoiding minerals sourced from the DRC is, for the foreseeable future, a practical impossibility. This market reality dismantles the logic of avoidance and reinforces the argument that the only viable path forward is through constructive and verifiable engagement to reform sourcing practices within the Great Lakes region.

The Cobalt Imperative: A Mathematical Certainty

The case of cobalt provides the most compelling evidence against the feasibility of disengagement. Cobalt is an essential component in the lithium-ion batteries that power a vast array of modern technologies, from smartphones and laptops to the rapidly expanding fleet of electric vehicles. The global supply of this critical mineral is overwhelmingly concentrated in the Democratic Republic of Congo.

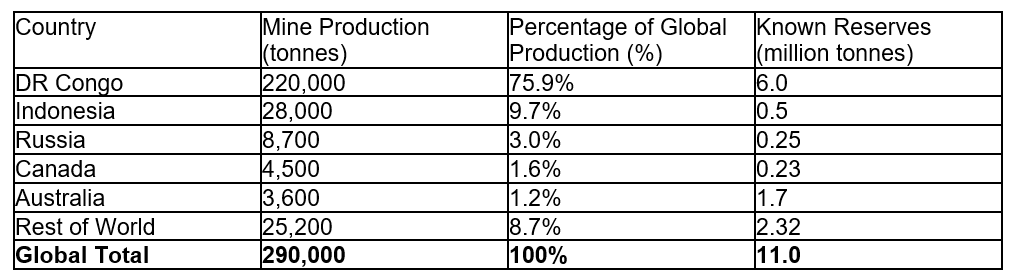

According to the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and other leading industry analysts, the DRC accounted for approximately 70-76% of the world’s total mined cobalt production in 2024. This dominance is not a fleeting market condition but a reflection of geological reality; the DRC holds over half of the world’s known cobalt reserves, estimated at 6 million metric tons. In stark contrast, the world’s other significant producers are far behind. Indonesia, the second-largest producer, contributes around 10% of the global supply, while established mining jurisdictions like Australia and Canada produce only about 3% and 2%, respectively.

The sheer scale of demand from a single company like Apple highlights the dependency on Congolese sources. Apple’s annual requirement for cobalt is estimated to be around 12,000 metric tons. This figure alone exceeds the combined annual production of Australia (3,600 tons) and Canada (4,500 tons). The data makes it unequivocally clear that there is no combination of alternative sources that can replace the DRC’s output and satisfy global demand.

Table 1: Global Cobalt Mine Production & Reserves (2024 Estimates)

This data provides an unassailable, fact-based foundation for the argument against disengagement. For global policymakers and corporate executives, the numbers demonstrate the mathematical impossibility of a “Congo-free” supply chain for cobalt-dependent industries. This reality is further underscored by a crucial detail in Apple’s recent policy directive. The company’s instruction to suspend sourcing explicitly names 3TG minerals but is conspicuously silent on cobalt. This selective approach is not an oversight; it is a tacit admission of reality. Apple cannot suspend its reliance on Congolese cobalt without crippling its ability to manufacture its most profitable products. This reveals the “suspension” policy not as a principled stand against sourcing from a conflict-affected region, but as a narrowly targeted legal maneuver focused on the specific minerals named in the DRC’s lawsuit. It exposes the disingenuous nature of the disengagement narrative, confirming that the global technology sector remains, and will remain, inextricably tied to Congolese cobalt.

The Limits of Recycling: An Inconvenient Truth for Corporate Narratives

In public-facing reports and sustainability initiatives, corporations heavily promote their efforts in recycling, creating a powerful narrative of circularity and environmental responsibility. Apple, for instance, has set ambitious goals to use 100% recycled cobalt in all its Apple-designed batteries by 2025 and has made significant progress in increasing the recycled content in its products. The growth in recycled battery metals is indeed a positive and rapidly advancing field.

However, this focus on recycling, while important, can function as a reputational shield, deflecting attention from the persistent and more challenging issues associated with primary mineral sourcing. The International Energy Agency (IEA), a leading authority on global energy systems, provides a critical and sobering perspective. In its analysis of critical minerals recycling, the IEA is explicit that while recycling is “indispensable,” it “does not eliminate the need for mining investment” and, crucially, “cannot replace the need for mined supply in the medium term”. The IEA projects that even with a successful and aggressive scale-up of recycling, the need for new mining investment will remain substantial, amounting to hundreds of billions of dollars through 2040.

This expert assessment reframes the debate. The choice is not a simple binary between “dirty” primary mining and “clean” recycling. For the foreseeable future, both are essential to meet the demands of the global energy and technology transitions. Therefore, the core challenge is not how to abandon primary mining, but how to reform it. Corporations cannot be allowed to use their commendable achievements in recycling to evade their fundamental responsibilities in the primary supply chain. The inconvenient truth is that engagement in regions like the DRC is not optional; it is a structural necessity that demands robust governance solutions, not avoidance.

A Flawed but Foundational Model: Deconstructing the Kimberley Process

In the search for a viable alternative to the failed model of voluntary due diligence, the Kimberley Process (KP) Certification Scheme for rough diamonds stands out as a critical, if imperfect, precedent. Established in 2003, the KP represents the only existing international regulatory framework that successfully implemented a binding, state-led system to control the trade of a conflict-linked resource. A thorough deconstruction of the KP—analyzing both its proven mechanics and its acknowledged limitations—provides an essential blueprint for designing a more effective and comprehensive certification system for 3TG, cobalt, and other critical minerals.

The Proven Mechanics of a State-Led System

The fundamental strength of the Kimberley Process lies in its mandatory, government-enforced structure. It is an international, multi-stakeholder trade regime that brings together governments, industry, and civil society in a tripartite partnership. Its effectiveness is rooted in a set of core principles that create hard, legally enforceable barriers to illicit trade, a stark contrast to the voluntary nature of corporate-led initiatives.

The central tenets of the KP model include:

1. A Binding, State-to-State Compact: Participation in the KP is a prerequisite for any country wishing to trade in rough diamonds. Member states, which collectively account for 99.8% of the global rough diamond trade, are legally bound to trade only with other participating members. This creates a nearly closed-loop system that effectively isolates non-compliant actors from the legitimate international market.

2. Enforceable Government Certificates: The system’s operational core is the Kimberley Process Certificate. All cross-border shipments of rough diamonds must be transported in tamper-proof containers and accompanied by an official, government-validated certificate that attests to their conflict-free origin. Importing authorities in member countries are legally obligated to reject any shipment that lacks this documentation, providing a clear and non-negotiable enforcement mechanism at the point of entry.

3. Peer Monitoring and Data Exchange: Member states are required to implement national legislation and internal controls to enforce the scheme’s provisions. Crucially, they commit to transparency through the regular exchange of production and trade statistics, which are subject to peer review visits and analysis. This peer-monitoring function creates a mechanism for mutual accountability among participating governments.

The primary success of this model is quantifiable and significant. Before the KP’s implementation, it was estimated that “conflict diamonds” accounted for as much as 15% of the total international trade in the late 1990s. Today, that figure has been reduced to less than 1%. This dramatic reduction demonstrates the profound efficacy of a system that conditions market access on verifiable compliance with internationally agreed-upon standards.

Acknowledging the Limitations: Lessons for a “KP 2.0”

To credibly propose the KP as a foundational model, it is essential to honestly address its well-documented flaws. These limitations are not fatal to the model itself but provide critical lessons for the design of a more robust and modern successor scheme for other minerals.

The most significant criticisms of the KP include:

● The Narrow Definition of “Conflict”: The KP’s founding documents define “conflict diamonds” specifically as “rough diamonds used by rebel movements or their allies to finance conflict aimed at undermining legitimate governments”. This definition was a product of the specific historical context of the wars in Sierra Leone and Angola. However, it creates a major loophole by excluding diamonds linked to violence, human rights abuses, or corruption perpetrated by state security forces or other actors not formally classified as “rebel groups.” This narrow scope has been a major point of contention for civil society organizations and has limited the KP’s ability to address a broader range of abuses within the diamond sector.

● Gaps in Broader Human Rights and Environmental Standards: The scheme’s focus is solely on rebel financing. It does not incorporate standards related to labor rights, child labor, worker health and safety, fair pay, or environmental degradation, all of which are significant issues in both artisanal and industrial mining.

● Traceability and Fungibility Challenges: A KP certificate applies to a sealed parcel containing a batch of rough diamonds, not to each individual stone. While this is a practical necessity, it creates a vulnerability in the system. Once a parcel is opened in a major trading hub, its contents can be mixed with diamonds from other sources, including illicit ones. Without a robust system for tracking individual stones or smaller batches post-export, the chain of custody can be broken, allowing laundered diamonds to enter the legitimate supply chain.

These flaws, however, should be understood as design choices reflective of the political compromises necessary to achieve consensus among dozens of sovereign states in 2003. They were pragmatic decisions made to solve the specific and urgent problem of rebel-funded wars. The key takeaway is not that the state-led model is inherently broken, but that its foundational principles must be updated. The success of the KP was in establishing the powerful precedent of state-enforced market exclusion as a tool of international governance. A future scheme for 3TG and cobalt can and must adopt this core principle while expanding the criteria for that exclusion. It must incorporate a broader, modern definition of conflict and human rights abuses, drawing from evolved international norms such as those articulated in the OECD Due Diligence Guidance. The KP’s limitations are not a reason to discard the model, but rather a clear roadmap for how to build a stronger, more comprehensive “KP 2.0” for the 21st century.

The Untapped Potential of Regional Architecture: Assessing the ICGLR’s Certification Mechanism

While the Kimberley Process provides a proven global enforcement model, the institutional architecture for implementing a similar scheme for critical minerals in Africa’s Great Lakes region already exists. The International Conference on the Great Lakes Region (ICGLR) and its Regional Certification Mechanism (RCM) offer a sophisticated, locally-owned framework that, despite its current underperformance, represents the most logical and viable vehicle for a new, binding certification system. Analyzing the RCM’s existing structure and identifying the precise reasons for its limited success reveals a clear path for targeted reforms that could unlock its full potential.

The RCM: A Framework in Waiting

Established by the 12 member states of the ICGLR, the RCM was designed as a comprehensive regional initiative to combat the illegal exploitation of natural resources and sever the link between mining and conflict. Its primary focus is on the so-called “3TG” minerals—tin, tantalum, tungsten, and gold—which have been most closely associated with financing armed groups in the eastern DRC.

The RCM is not a single tool but an integrated system comprising six key components: (1) the Regional Certification Mechanism itself; (2) the harmonization of national mining legislation among member states; (3) a regional database to track mineral flows; (4) programs to formalize the artisanal and small-scale mining (ASM) sector; (5) promotion of the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI); and (6) a whistle-blowing mechanism to report illicit activities.

The mechanism’s standards are explicitly based on the internationally recognized OECD Due Diligence Guidance. Its stated goal is to ensure that mineral supply chains provide no direct or indirect support to non-state armed groups or to public or private security forces engaged in illegal activities or serious human rights abuses. Operationally, the RCM includes detailed procedures for the inspection and validation of mine sites, which are classified as Certified (Green), provisionally compliant (Yellow), or non-compliant (Red). It also outlines requirements for establishing a verifiable chain of custody from these validated mine sites to the point of export, culminating in the issuance of an ICGLR Certificate for compliant shipments. This demonstrates a high level of technical sophistication and a clear understanding of the on-the-ground realities of mineral traceability in the region.

Identifying the Gaps: Why the RCM Has Underperformed

Despite its well-conceived design, expert consensus holds that the RCM has failed to achieve its objectives fully. It is widely described as “patchy, under-implemented, and hindered by political and regulatory gaps”. While some successes have been noted in reducing the presence of armed groups in specific, well-controlled supply chains, the overall system has not succeeded in eliminating the broader problems of mineral smuggling and laundering.

The critical failure point, as identified in the initial analysis, is the “uneven downstream uptake by global electronics” and other end-user industries. This points to the RCM’s primary structural weakness: it lacks the enforcement “teeth” of the Kimberley Process. The RCM’s authority effectively ends at the African port of export. While an ICGLR Certificate provides a level of assurance for buyers, there is no corresponding mandatory import control regime in the major consumer markets of North America, Europe, and Asia.

This absence of binding international leverage renders compliance effectively voluntary for downstream companies. A global manufacturer or smelter may face reputational risk or pressure from NGOs for sourcing minerals without an ICGLR Certificate, but they do not face the hard legal barrier to market access that the KP imposes on the diamond trade. The KP’s power derives from the fact that a U.S. or EU customs official is legally required to seize any rough diamond shipment lacking a valid KP Certificate. No such legal requirement exists for a shipment of coltan or cassiterite lacking an ICGLR Certificate.

This fundamental difference is the primary reason for the RCM’s “uneven uptake” and its ultimate inability to make laundering economically and legally unviable. Illicitly sourced minerals can still be smuggled out of the region and introduced into the global supply chain because there is no foolproof mechanism to stop them at the borders of consumer countries. The RCM has created a sophisticated lock (the certificate) but has failed to convince the international community to install the corresponding keyhole (mandatory import controls). This missing piece is what has relegated a promising regional initiative to a state of partial effectiveness, leaving the door open for “paper-clean” minerals to continue contaminating global supply chains.

The Path Forward: Translating KP Mechanics for Critical Minerals in the Great Lakes Region

The analysis of the failures of voluntary due diligence, the market realities of critical minerals, the foundational strengths of the Kimberley Process, and the untapped potential of the ICGLR framework leads to a clear and actionable policy conclusion. The international community must move beyond the current fragmented and ineffective system and build a new, integrated paradigm for mineral governance. This requires a pragmatic synthesis: translating the proven enforcement mechanics of the KP into the specific context of critical minerals and embedding them within the existing regional architecture of the ICGLR. This hybrid model offers the most credible path toward creating truly secure, transparent, and conflict-free mineral supply chains.

A Blueprint for a Fit-for-Purpose Certification Scheme

The creation of a robust “KP-ICGLR Hybrid Model” would involve a series of targeted reforms designed to merge the strengths of both systems while correcting their respective weaknesses. This would transform the RCM from a well-intentioned but underpowered regional standard into a globally binding regulatory instrument.

The key adaptations required are:

1. Expand the Mandate to Cover All Critical Minerals: The scheme’s scope must be officially and dynamically expanded beyond the original 3TG. The mandate should explicitly include cobalt, given its immediate strategic importance, and establish a clear process for adding other minerals, such as lithium, copper, and rare earth elements, as their extraction in the region scales up and associated risks emerge.

2. Adopt a Broader, Modern Definition of Conflict and Human Rights Abuse: The new scheme must learn directly from the most significant failing of the KP. It must formally discard the narrow definition of “rebel groups” and instead adopt the comprehensive risk framework outlined in Annex II of the OECD Due Diligence Guidance. This would expand the definition of unacceptable activities to include serious human rights abuses (such as torture, forced labor, and child labor), as well as direct or indirect support to any non-state armed group or illicitly acting public or private security forces. This ensures the system addresses the full spectrum of potential harms, not just a narrow subset.

3. Establish a Legally Binding Global Framework: This is the most critical and transformative step. Major mineral importing countries and economic blocs—principally the United States, the European Union, China, Japan, and South Korea—must enact domestic legislation that recognizes the ICGLR Certificate as the sole legal instrument for verifying the legitimate origin of designated minerals from the Great Lakes region. This legislation would make it illegal to import these minerals without a valid, government-issued ICGLR Certificate, thereby replicating the core enforcement mechanism that gives the KP its power. This creates a hard economic incentive for all actors in the supply chain, from the mine site to the final product manufacturer, to ensure compliance.

4. Strengthen and Formalize Tripartite Oversight: The governance structure of the RCM must be enhanced to mirror the KP’s tripartite model. While the ICGLR is an intergovernmental body, the roles of international industry associations (representing downstream users) and civil society organizations must be formalized within its oversight, audit, and standards-setting committees. This ensures greater transparency, enhances credibility, and leverages the expertise of all key stakeholders in monitoring and improving the system’s performance.

Addressing the Challenge: Bulk Minerals vs. High-Value Gemstones

A common critique leveled against adapting the KP model is the fundamental physical difference between the commodities. Diamonds are high-value, low-volume gemstones that can, in some cases, be individually tracked. In contrast, minerals like tin ore (cassiterite) or tantalum ore (coltan) are lower-value, high-volume bulk commodities that are fungible and cannot be geochemically “fingerprinted” back to a specific mine with certainty.

This critique, however, fundamentally misunderstands the source of the KP’s effectiveness. The power of the Kimberley Process is not derived from the scientific traceability of individual diamonds. Indeed, even within the diamond trade, tracing a single stone’s origin after it has been mixed in a parcel is notoriously difficult. The KP’s strength lies in its creation of a secure, state-audited chain of custody. It validates the integrity of the paper trail that accompanies a sealed, tamper-proof parcel of minerals from a compliant production area to the point of export.

This principle is directly and fully transferable to bulk minerals. The objective is not to geochemically analyze every kilogram of coltan. The objective is to ensure that a 50-tonne shipment of tantalum ore being exported with an ICGLR Certificate from a port in Tanzania can be irrefutably traced back through a documented and independently audited series of transactions to a specific set of ICGLR-inspected and “Green Flagged” mine sites in, for example, the DRC’s South Kivu province. The system controls the flow of documented, bagged-and-tagged material. The ICGLR’s existing framework already contains the basic architecture for this mine-site validation and chain-of-custody tracking. The KP model simply adds the missing piece: the binding international enforcement that makes falsifying that paper trail or smuggling uncertified material a legally and economically non-viable activity.

A Comparative Vision for the Future of Mineral Governance

The proposed hybrid model is not a radical invention but a pragmatic evolution, synthesizing the best elements of existing frameworks to create a system that is more robust, comprehensive, and effective than any of its predecessors. A comparative analysis makes the logic of this approach clear.

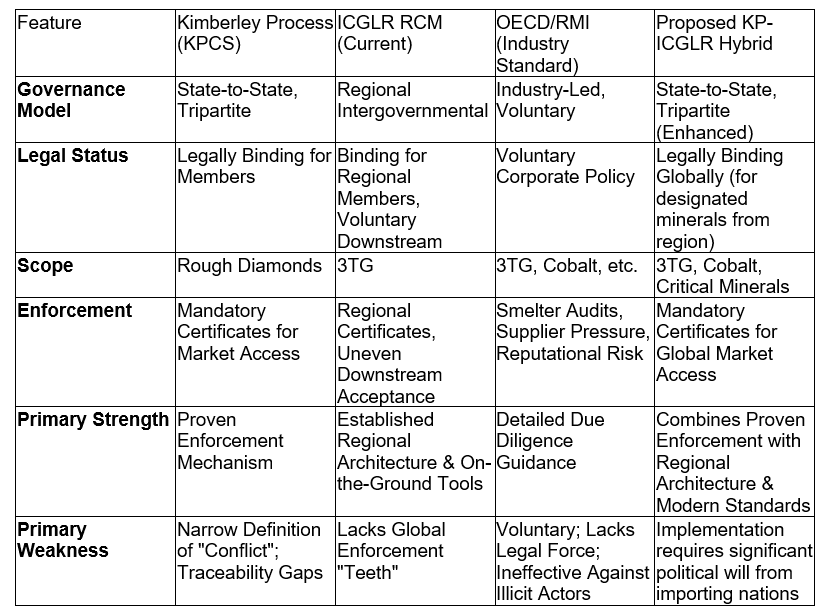

Table 2: Comparative Analysis of Mineral Certification Frameworks

This comparison crystallizes the central argument of this report. The current system, dominated by the voluntary OECD/RMI approach, provides excellent guidance but lacks the legal force necessary to compel compliance from illicit actors or to create true market certainty. The ICGLR RCM has the right regional tools but lacks global reach. The KP has the global enforcement power but is limited by an outdated scope and definition. The proposed KP-ICGLR Hybrid Model directly addresses the weaknesses of each system by combining their respective strengths, creating a comprehensive solution that is both technically sound and legally enforceable.

Conclusion: From Avoidance to Verifiable Engagement

The era of relying on voluntary corporate commitments and opaque, audit-based due diligence to govern the world’s most sensitive mineral supply chains is over. This model has failed. It has failed to bring lasting peace and security to the mineral-rich communities of the Great Lakes region, it has failed to provide downstream industries with genuine certainty about the integrity of their products, and it has failed to satisfy the growing demands of consumers and regulators for true accountability. Corporate strategies of disengagement and de-risking are not a solution; they are an abdication of responsibility that punishes legitimate actors and pushes the illicit trade deeper into the shadows, exacerbating the very problems they claim to solve.

The geological and economic realities of the 21st century—driven by the twin imperatives of the digital revolution and the clean energy transition—make the Democratic Republic of Congo and its neighbors indispensable partners in the global economy. Avoidance is not a credible long-term strategy. The only practical, ethical, and sustainable path forward is one of renewed and robust engagement.

This report has laid out a blueprint for such an engagement: a paradigm shift from voluntary self-regulation to binding, state-led governance. By translating the core enforcement mechanics of the Kimberley Process Certification Scheme into the institutional framework of the ICGLR’s Regional Certification Mechanism, the international community can build a fit-for-purpose system for 3TG, cobalt, and other critical minerals. Such a system, underpinned by mandatory import controls in consumer countries and expanded to include modern human rights standards, would finally create the conditions where laundering becomes economically and legally unviable.

Achieving this vision requires collective political will. It requires producing nations in the Great Lakes region to continue strengthening their internal controls and governance. It requires downstream industries in the technology, automotive, and energy sectors to move beyond public relations and actively support a binding regulatory framework that creates a level playing field for all. And, most critically, it requires governments in the major importing nations to recognize that supply chain security and ethical responsibility are two sides of the same coin, and to enact the legislation necessary to give this new system global force. The time has come to work collaboratively to build a system that transforms Africa’s immense mineral wealth from a source of conflict into a durable engine of peace, prosperity, and sustainable development for its people.